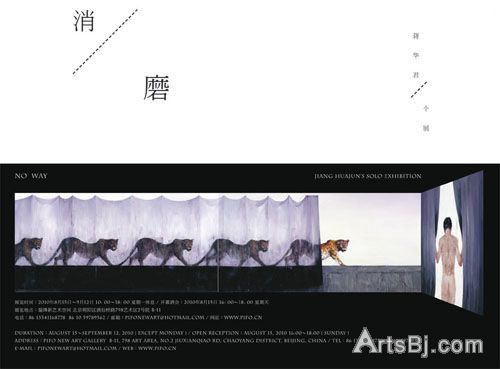

作者:蒋岳红

在我们已经习惯了在当代艺术作品中去寻找个人存在与其存在状况之间林林总总的“妥协”方式和“妥协”结果时,遭遇蒋华君的绘画,会让我们重生疑问:当抒情或多或少已经成为当代绘画实践所刻意回避或者突破的框架时,画家执意于个人的内心感验,执意于画面关于成长和缺失的主题性表达,执意于以传统的观看方式来打动观看者的现实意义究竟何为?

蒋华君的作品在当代艺术实践的考察中或许可以算是一个“异数”,既无关乎绘画本体语言形式的抢眼,也无关乎绘画观念表达策略性的矫饰,却是真切地以一个已然内化的现代艺术家情怀将其自身对于周遭生活的体悟和思虑挥斥在画布上,将现世生存境遇中的关乎缺失和默守的精神困局视觉化地呈现出来,凭直觉和本能构建出一个完全个人化的画界。当然,蒋华君的现代艺术家情怀更多地是与其对于个体生存主题的关注,而不是绘画形式的前卫概念相关联。相对绘画语言的创新和见识的深刻性,他或许更想要追求的是如何将作为个体在生活消磨中萌生的抵抗意志淋漓地传达出来。

无论是绘画进入书写的过去的黄金时代,还是不乏期许的未来的美好时代,都远离蒋华君的绘画现实境遇——这里是一个危机四伏的怀疑时代——如果说眼见的那些得以写入艺术史能提供给我们的应对艺术危机的出口其实从来都不是集体经验而是个体选择。比如能在文艺复兴的完美之下破坏规则的是丁托雷托1出人意外的布局,是格列柯2的变形和色彩的不正确,以及在题材上另辟蹊径的荷尔拜因3的肖像画和布鲁盖尔4的风俗画;能在印象派的喧嚣热闹之后先行一步的是三个特立独行的遗世者5。那么,我们是否也有理由相信艺术作品在日益成为图像志之后,在越发追求禅意和无为之外,同样需要一种来自直接经验的个人风景。或许这也是为什么在材料应用,题材选择和观看方式上都足以让艺术别开生面的立体派却终究会被“低估”的缘由——在那里,个人风格已经被取消了。

因此,蒋华君对于个人抒情方式的坚守,除了与他自身所触知的当下状况相关之外,也是对于当代绘画“主流”策略的一种自觉的抵抗——与选择性表达的“妥协”相比,他的绘画表达显露更多的是经验而不是知识,是感受而不是梳理,是率性而非刻意。在他这里,抒情因为受限而成为了必需。他通过绘画的表达与观看者对视,其内心视象倾心讲述和传达出的是关乎其自身,也关乎我们的成长的心悸、怅惘和荒诞。

于是,正因为艺术家自觉流露出来的不断滋生的抵抗之心,使得艺术家的个人风景是否能别样动人,艺术家的内心视象是否能意味深长,开始成为了我们的期待。

Since Emotionalism Has Been Endless

By Jiang, Yuehong

Since we have been used to looking from the contemporary arts for divers solution and outcomes of “compromise” between an individual being and his existing status, we will be led by an encounter of Jiang Huajun’s art to a doubt again: whereas emotionalism has more or less been a frame that the contemporary art practices are intended to obviate or break through, what kind of value in reality is there then if a painter engages himself fully in esteeming his inside feeling and experience, his obvious motif on growth and emptiness in life, and an audience’s excitement from a traditional view?

In a survey of the contemporary practices, Jiang’s art probably counts as a “different figure”, independent of an eye-catching trait of painting language itself as well as of a priggish strategy for delivering an art notion. With a contemporary artist’s passion that he has already taken into his inner world, his art is truly a flourish of his own understanding and thoughtfulness about his own life status on canvas, presenting a visualized dilemma of human spirit being vacant, lost and tacit in the worldly survival today, which constructs an art space absolutely individualized with his own intuition and instinct. Indeed, it is his concern of individual existence as a motif rather than about any avant-garde notion of art form that is correlated to his passion of a contemporary artist. Rather to any innovation in painting language or depth in insight, he perhaps prefers seeking an unlimited delivery of a resisting will that germinates from an individual’s wearing-down in life.

No matter that painting was or will be in the gold era of record in the past or in a nice era not lack of good will in future, it is far from the realistic status where Jiang’s art comes out – a statue in an age of suspicion with full of crises – if we say that those already seen and written into the art history can offer us any ideas of handling art crises, those ideas should be always from individual choices rather than from collective experiences. For instance, it is Tintoretto6’s unexpected overall arrangement, El Greco7’s distortion and incorrectness of coloring, Hans Holbein8’s exclusive subjects of portraiture and Pieter Bruegel9’s genre painting that respectively breaks the perfect formula of Renaissance, and it is the three aloof figures (Paul Cezanne, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin)10 who went forth first after the Impressionism’s uproarious revelry. Shan’t we evidently believe, then, that the arts also need certain individual views originating from direct experience since they have had a growing trend of being records of images with a seek of Zen or inaction in theme? Perhaps this also explains why the cubism was “undervalued” in the end at all, even though its material application, subject choice and view pattern significantly enable art to have something fairly new – there, all individual styles are already cancelled.

Thus, Jiang’s holding his ground of his own emotionalism is not only connected to the current status felt and realized by his own but also his self-consciousness of resistance against the “main-stream” of the contemporary art strategy – compared with any selective delivery as a “compromise”, Jiang’s art delivery exposes his experience rather than learning, his feeling rather than reasoning, his frankness rather than intention. To him, emotionalism turns to be a need just because it has been endless. Via his painting expression, he and his audience gaze at each other in eye. What the visions from his inside world tell and convey to their utmost are about himself as well as about the palpitating, distracted and nonsensical feelings along with our growth.

And then, it is because a will of resistance consciously conveyed by the artist has been constantly yielding that we start in hopes of such a will making his individual view exclusively touching and his inner visions fairly significant.

(translated by Jiang, Wenhui)[NextPage]

1 Tintoretto,1518-1594

2 El Greco,1541?-1614

3 Hans Holbein the Younger,1497-1543

4 Pieter Bruegel the Elder,1525?-1569

5 Paul Cezanne,1839-1906;Vincent van Gogh,1853-1890;Paul Gauguin,1848-1903

6 Tintoretto,1518-1594

7 El Greco,1541?-1614

8 Hans Holbein the Younger,1497-1543

9 Pieter Bruegel the Elder,1525?-1569

10 Paul Cezanne,1839-1906;Vincent van Gogh,1853-1890;Paul Gauguin,1848-1903

(编辑:罗谦)

版权声明:

本文系北京文艺网独家稿件。欢迎转载,请务必注明出处(北京文艺网)及作者,否则必将追究法律责任。